On the 4th January 1806 the lookout stationed on Signal Hill spotted sails appearing over the horizon and immediately sent a message to General Jan Willem Janssens in Cape Town of the approaching flotilla. The fleet had been expected after two French ships, the Atlanta and the Napoleon had arrived in the Cape the month before. They had mentioned that they had passed a large fleet of British ships heading south and Janssens knew he was about to be attacked. Cape Town was about to enter the history books as part of the Napoleonic wars.

The fleet was under the command of Captain Sir Home Riggs Popham who had been given nine ships of the line to escort fifty-four transport ships laden with men and supplies. The task was to take the Cape from the defending Batavian Republic and to ensure that Napoleon’s fleet could not gain a port which would endanger the British commercial route around the Cape of Good Hope. On board the transports were an army under the leadership of Lt-General Sir David Baird, a man with previous experience of the defences of the Cape and a man well known for expertise in leading campaigns in the southern oceans. Expecting the Batavians to have a defending force in excess of 5000 men, Baird had insisted that he needed 6000 men at least to capture the Cape. Through recruiting en-route he arrived in the Cape with just over 6,500 in seven foot regiments and a squadron of dragoons.

In the evening of the 4th January the large fleet anchored in the lee of Robben Island. Baird had warned Popham of the deadly hot shot that the forts around Table Bay could fire and not to enter anywhere near safe anchorages of the bay. At 1:00am on the 5th Baird gave the order for the first landing party to man the boats with the 59th Regiment and the dragoons being given the task of setting up a bridgehead at Big Bay. With difficult conditions, the sailors struggled to row the 7 miles from the ships to Big Bay. When attempting to land the boats it was evident that the surf and shallow waters were not favourable and the boats were turned around and back to the fleet.

Baird called a meeting of his commanders to discuss an alternative plan, should they be unable to land the troops from the anchorage at Robben Island. He ordered General Beresford to take the dragoons and the 38th Regiment north and to land at Saldanha Bay where he knew there were large farms which could supply the horseless dragoons with the required steeds. They would then march south and meet up with Baird who hoped to land the remaining troops closer to Cape Town. In the late afternoon of the 5th nine of the transports along with HMS L’Espoir sailed north to Saldanha Bay.

On the morning of the 6th the weather had calmed enough for Baird to be confident of getting his men on shore. Having decided that Big Bay was not suitable: the men of the Highland regiments were ordered to make for Losperds Bay, the area now known as Melkbosstrand. The three regiments were loaded on to the large rowing boats and headed for the shore where they were met by local militia waiting in the sand dunes. The initial landing was not good for the Scottish troops and one of the first landing boats hit rocks and capsized, all 37 soldiers and 15 sailors drowned before getting to the shore. The following boats had more success and despite a skirmish on the beach with the defenders the British troops soon gained a foothold and established a landing place for the invading army to disembark. Popham sacrificed one of the smaller transports by beaching the ship to provide a breakwater for the boats to come and go. Over the next 24 hours Baird landed 4,500 men on to the beach ready to march on Cape Town.

After getting the message from Signal Hill, General Janssens had sent out a cannon fire from the Castle to alert the outlaying residents of the arrival of the fleet. Within hours Burger Militia as far away as Swellendam had received the message and were mustering to head to Cape Town and to defend their lands from the invading forces.

Over the next couple of days men arrived in the town to give Janssens a total of 3,122 men of different backgrounds to defend the Cape. Leaving a holding force under the command of Lieutenant Colonel von Prophalow, Janssens left the Castle and arrived at Rietvlei on the 7th January with just a meagre contingent of 2061 men of differing nationalities. Under his command were three recognised regiments of men, the 22nd Batavians, Hottentot Light Infantry and the 5th battalion Waldeckers who were professional soldiers from the Principality of Waldeck: within the German Empire. Along with these men were a naval contingent from the two French ships and an artillery manned by Javanese and Malays under the command of Lieutenant Pellegrini. In addition, dragoons from Swellendam and Stellenbosch gave Janssens a mobile accessory which could keep an advancing force at bay with accurate shooting by skilled horsemen. From Rietvlei: Janssens took his men up the road from the camp and camped the night at Blaauwbergsvallei Outspan, in readiness for an advance on the British the next morning thereby hoping to gain an advantage by occupying the high ground looking down on to Losperds Bay.

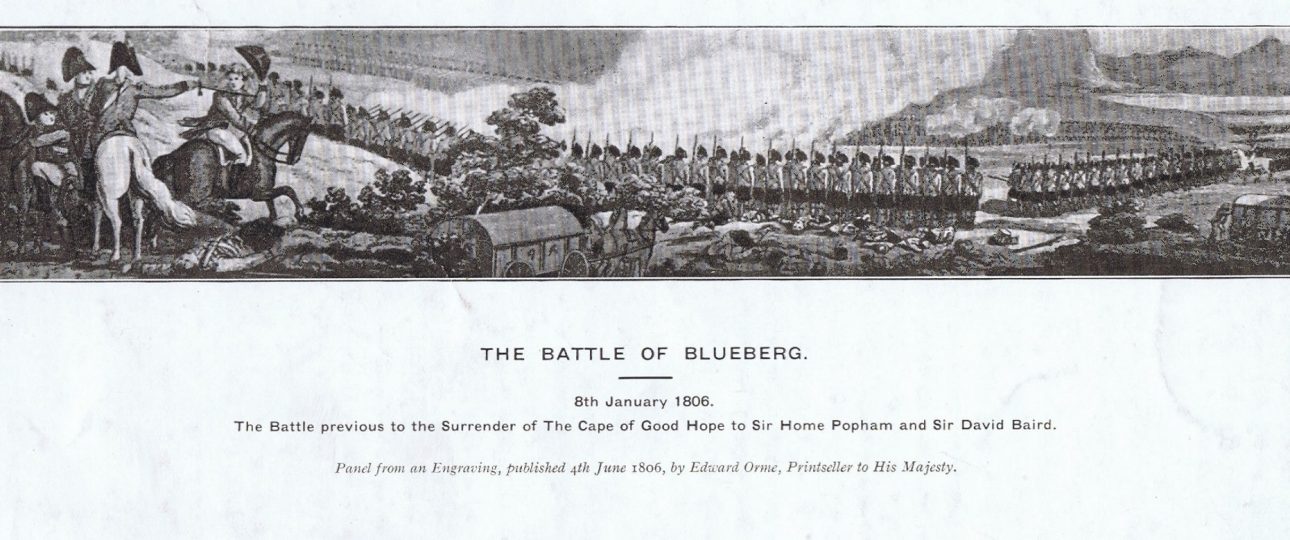

In the early hours of Wednesday 8th January 1806 both armies left their overnight camps and headed towards each other. After leaving the camp at Blaauwbergsvallei with the sun just appearing over the eastern high ground Janssens was soon to see the redcoats of the British emerging in two columns, he had no option but to set up his men in a defensive line from the sand dunes below Blaauwberg and across the junction of roads that the British were looking to use to advance on Cape Town.

Baird had stolen Janssens’ thunder by mobilizing his men at a very early hour and forming them in to two brigades. The 1st Brigade was under the command of his brother Joseph, in the absence of General Beresford, and comprised the 24th, 59th and 83rd regiments of foot. They were to advance through the saddle between Blaauwberg Hill and the small hillock to the east taking with them the few artillery pieces that Baird could call on. These guns, two howitzers and six field guns had to be man-hauled by sailors as only the officers had any horses that could be called upon. The 2nd Brigade was under the command of General Fergusson and comprised the 71st, 72nd and 93rd regiments of foot, all being Scottish and therefore known as the Highland Brigade.

Baird took up a position on the hillock to the east of Blaauwberg and seeing the Batavian forces lined up on the plain ordered Fergusson to form the Highland Brigade in to their ranks. 2,000 Highlanders in four rows spread out in the fynbos and prepared to advance on the defensive forces. The howitzers were brought up on to a high point behind the advancing Highlanders and the battle began with them firing over the Highland brigade – targeting the Batavian central line. As the Highlanders advanced so the grenadiers of the 24th regiment skirted along the lower slope of Blaauwberg and advanced on to the smaller Kleinberg. Seeing the possible flanking movement of the British, Jannsens ordered the Swellendam Militia to ride to the top of Kleinberg to cut them off. There were now two points of conflict unfolding on the same battlefield.

Janssens rode along the line of the Batavian force spread out across the road, with his Artillery and dragoons holding the right flank, sand dunes with Hottentot LI sharpshooters protecting his left. In the centre of the line he was depending on the Waldeckers. Shouting words of encouragement, the men cheered Janssens as he rode past, all except the Waldeckers who in the opening salvos from the British guns had already borne several losses.

At about 100 yards from the defending line the Highlanders were ordered to load their Brown Bess muskets, and a volley of heavy musket balls headed towards the Batavians. The range was too far to be effective, but a thick white cloud, produced by the black powder charges, created a perfect screen for the men to fix bayonets and charge. The guns were now firing from both sides and men began to fall as the two armies came together. At this point the nerve of the Waldeckers broke, and no orders from Janssens could rally them to stand against the advancing Scotsmen. The Waldeckers turned and the centre position of the Batavian defensive line was open and immediately exploited by the attackers.

Janssens ordered his remaining troops to fall back in a hope of closing the gap as the Highlanders reached the broken line, but despite continued firing from Pellegrini’s artillery position the Batavian force could not hold any longer. The remaining defenders pulled back altogether, and the exhausted Highland Brigade halted where once the last line of defenders had been.

As the fight concluded on the flat plain below Blaauwberg the 24th regiment grenadiers were advancing up the slopes towards the Swellendam Dragoons on Kleinberg. In the front was their officer Captain Andrew Foster. As with several of the British officers that day he was mounted and made an easy target for the expert shots of the Burger militia. Foster was hit and fell from his horse, the only British officer to lose his life in the battle that day. Foster’s horse became a trophy for the Swellendamers who then retreated back to Rietvlei to meet up with their General.

The battle of Blaauwberg was over costing the lives of over 300 men of all nations on the day, and probably three times as many over the next weeks from wounds inflicted.

Janssens retreated up to the Hottentot Holland Mountains with a depleted army, releasing many of his Burgers as it was harvest time. The Waldeckers had already been sent back to Cape Town in disgrace.

After re-grouping at Rietvlei on the evening of the 8th Baird marched his Army on towards Cape Town where he was met by Von Prophalow who on the 10th January, signed an agreement of capitulation on the Town. After his long march south from Saldanha Bay, Beresford was given the task of searching for Janssens and on the 17th January the two men met in the Hottentot Holland mountains. The following day Janssens signed the final articles of capitulation ending the centuries long hold on the Cape by the Dutch.